Walking In Memphis (Again) with MLK Jr.

They say the birds don’t sing at Auschwitz. You *might* think the same would be true of the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

A few years ago, someone in a bar told that Memphis is home to two things:

Elvis Presley and violence.

I didn’t understand what he meant at the time, and maybe I still don’t. Let’s just say that the guy wasn’t exactly in a fit state to elaborate. His statement wasn’t a million miles away from something Shawn Amos once said about the city:

Memphis is the place where rock was born and Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. It's full of contradictions, abject poverty, and riches that only music can provide.

I took a trip there in 2019 that brought me a little closer to understanding the city, which has some of the highest rates of murders and violent crime in the USA. But, as you’ll see from the below, the place remains a bit of an enigma to me.

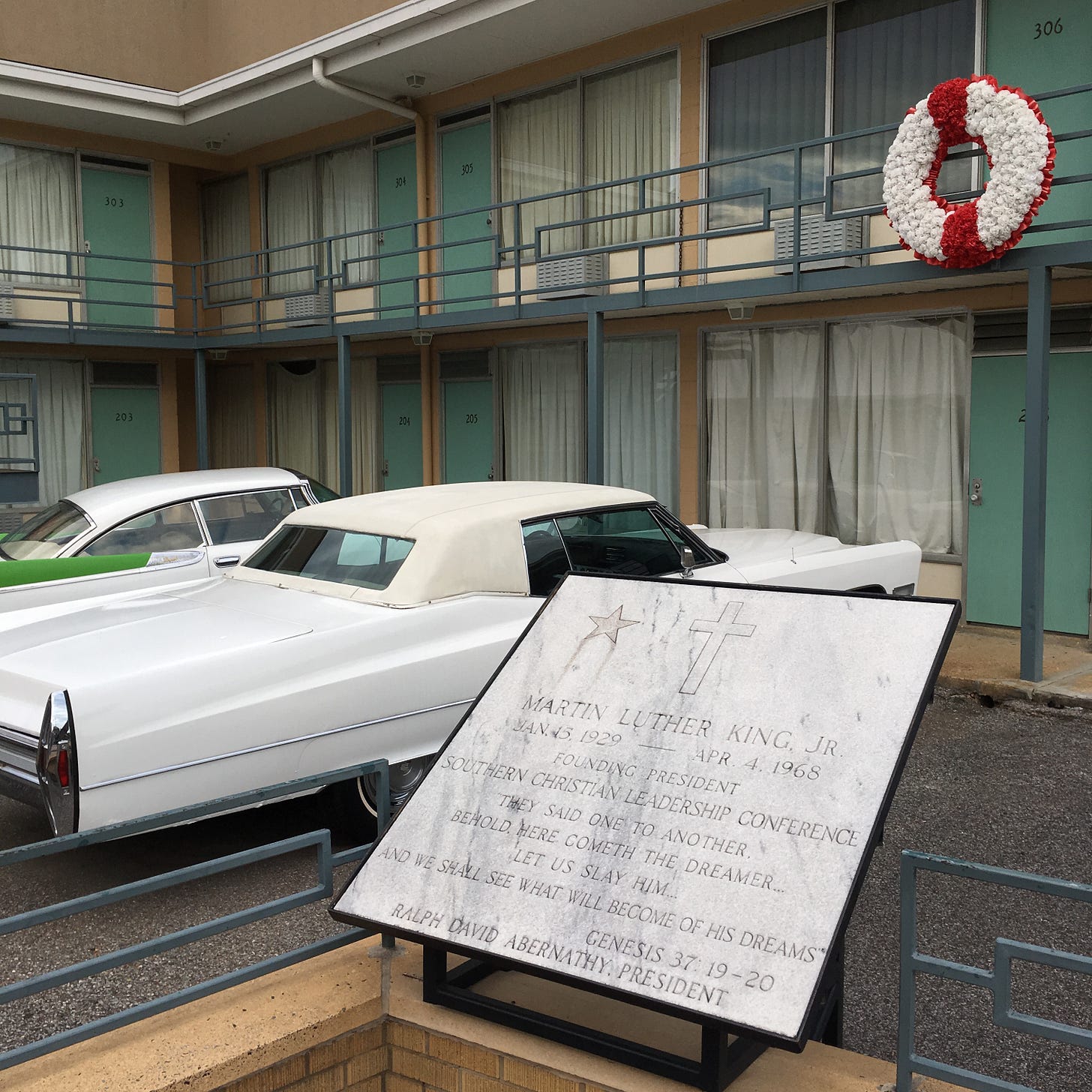

Photo by Author

Early on in my trip I visited the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in 1968 after being drawn to the city by the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike. It was an extremely sombre experience…at least for a little while.

Until an African American woman handed her smartphone to her young son and hopped over a low brick wall. She lay across the bonnet of a vintage car, like Tawny Kitaen on Whitesnake’s Jaguar XJ, and said “Darnell, get a shot of this for me!”

Darnell looked a little hesitant, but dutifully started snapping pictures of his mother spread-eagle on the hood of the 1968 Cadillac. Looking again at images from the Lorraine I see the vehicles are parked facing the motel, so she must have been on the trunk. A minor betrayal of my memory.

I glanced around but there was no-one else nearby. Despite feeling deeply uncomfortable at this disrespectful behaviour, I said nothing. Why is that? Well, it could just be that I’m a coward.

Or did I, as a white man, feel uncomfortable intruding into (what some would term) a Black historical site and telling a Black woman how she should be acting?

Maybe I didn’t say anything for the same reason I didn’t put this post live on Martin Luther King Jr. Day one week ago today – I didn’t feel like my voice, that of a British white man, was one that needed to be heard at that moment. However, there’s a problem inherent in that statement.

Photo by Author

Allyship – whether with the Black community, LGBTQ folks, or any marginalised group – is performative by definition. And it has to be that way, because silence and inactivity has been perceived as complicity and complacency for such a long time.

But by demonstrating our allyship, we risk making it all about us. Remember when (well-meaning) white Instagram users inadvertently drowned out African American voices and businesses using the #blackouttuesday hashtag underneath their black squares.

In a Netflix comedy special Anthony Jeslnik makes the compelling argument that, when people respond to tragedies with thoughts and prayers, what they’re really saying is:

Don’t forget about me today.

So what is the right move here? As far as I can see, it should be to elevate voices that have something to say about these issues. My platform on Substack is small right now, but that’s an undertaking I’ll be working on in the future.

Near the Lorraine Motel I encountered a woman at a small table covered with a plastic sheet, adorned with an array of pamphlets and binders. I’d later learn that this woman was Jacqueline Smith, who has spent more than 30 years protesting her forced eviction from the building.

The BBC’s Harry Low calls Smith “the woman still protesting over Martin Luther King”, but that’s not exactly true. She’s protesting her eviction but, on a larger scale, she’s protesting the gentrification of Memphis and the commodification of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death as well.

Anyone can, for example, hire the Lorraine Motel to host an event there.

Jaqueline was quiet on the day of my visit. I don’t blame her for that; I’m sure that protesting for 11,000 of them in a row is exhausting. I didn’t know about the magnitude of her undertaking at the time and, looking back, I wish I’d asked a few more questions and just listened to her.

Photo by Author

Down the street I quenched my thirst with a quick drink at Earnestine & Hazel’s, which Thrillist once called America’s greatest burger dive bar. I didn’t get as far as chowing down on a Soul Burger, because something felt wrong the second I walked in the place.

I’m talking immediate goosebumps and hairs standing up on the back of my neck.

A one-time brothel, in which 13 people have died over the years, Earnestine & Hazel’s is reportedly one of the most haunted buildings in Memphis, Tennessee. And I felt that, like I was being watched, as soon as I walked through the door. I drank up and got out of there quickly.

In 2021, the compact burger joint was sold to investors for more than $1 million.

When I think of a British ghost, I think of a Victorian lady with one of those frilly parasols. Or maybe a chimney sweep wearing a newsboy cap. When I think about American ghosts, I lean more contemporary.

Someone younger and full of hurt, maybe even rage. A Black man, perhaps?

Salman Rushdie put it beautifully when he said:

Now I know what a ghost is. Unfinished business, that’s what.

I don’t know how to exorcise all of the “unfinished business” in America, which is almost palpable in cities like Savannah, Memphis and New Orleans. Time? Progress? Acknowledgement? I’ve always thought that it’ll come in due course but, sometimes, it feels further away than ever.